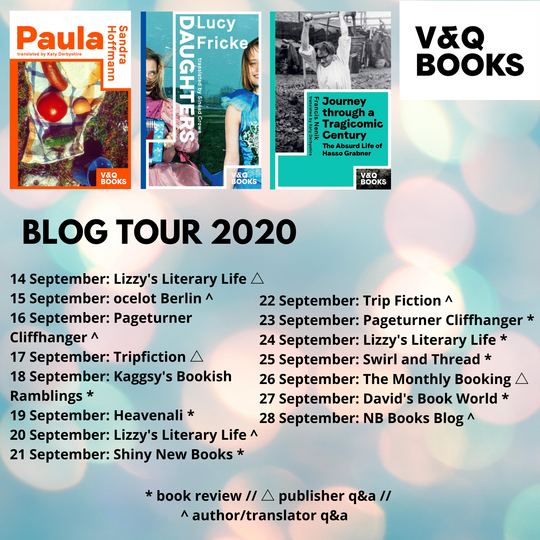

My post today is part of a blog tour for V&Q Books, the new English-language imprint from the German publisher Voland & Quist. The imprint is headed by the translator Katy Derbyshire, and is dedicated to writing from Germany. It’s not necessarily going to be limited to books translated from German, although the first ones are. V&Q offered me review copies of their first three titles, and I take a look at each below…

***

Sandra Hoffmann, Paula (2017)

Translated from the German by Katy Derbyshire (2020)

Paula begins like this:

We have a word in German: schweigen. It means deliberately remaining silent; it is different to merely being quiet.

This autobiographical work explores the effects such a deliberate silence may have on a family. The young Sandra Hoffmann knew that she and her mother looked different from other people in her village – darker-skinned – but she didn’t know who her grandfather was. Her grandmother Paula, a staunch Catholic, refused to say.

This isn’t a story of Hoffmann discovering her grandfather’s identity. It’s a study of the gaps left behind and what might fill them. Hoffmann goes over the many photographs that Paula left behind, and imagines the scenes and people in them.

The silence – the schweigen – permeates the book, spreading through its long passages. The oppressive effects of the silence on family life, in Hoffmann’s childhood and down the years, are vividly conveyed.

Lucy Fricke, Daughters (2018)

Translated from the German by Sinéad Crowe (2020)

Daughters is the story of two women – old friends – trying to find their place in life at age forty, and to deal with the loss of a father-figure.

For Martha, this loss is imminent: her father has booked an appointment for a one-way journey to Switzerland, and wants her to drive him. Betty wants to visit Rome to find the grave, not of her biological father (with whom she has little to do), but an ex-partner of her mother’s, an Italian she remembers as “the Trombonist”. Martha and Betty embark on a road trip across Europe with these intentions in mind. But both of them will find that the situation is not as they imagined, and their relationships will be tested.

Lucy Fricke’s novel is full of wry humour that makes it a pleasure to read:

We were the daughters of fathers who’d only found time to talk to us after they’d retired. We explained the internet to them and they explained the weather. Their love came so late that we barely knew what to do with it. We just accepted it with gratitude. But we had little to give, and nothing at all to give back.

Sinéad Crowe’s translation is wonderful: so often, I found myself stopping at a striking turn of phrase. The plot veers off in unexpected directions… This book is a joy.

Francis Nenik, Journey through a Tragicomic Century (2018)

Translated from the German by Katy Derbyshire (2020)

This non-fiction volume is subtitled “The Absurd Life of Hasso Grabner”. Grabner (1911-76) was a writer, albeit an obscure one – Francis Nenik says that he wanted to write about a forgotten author, and there was barely anything about Grabner online at the time he looked.

The reason Grabner’s life is described as absurd has to do, I think, with its apparent contradictions. He was a committed young communist who ended up being awarded an Iron Cross by Germany for his military service. He was director of a steelworks in the GDR whose writing was banned.

As with Fricke’s book, there’s a wonderfully wry undercurrent – a fine translation by Katy Derbyshire:

And Hasso Grabner? Not only is he part of the grotesque named history and always precisely where it is being made; he is also co-writing it, even though he doesn’t know the script, and history is more than slippery, what with it only ever coming about when it’s already happened…

You can watch a reading from Journey through a Tragicomic Century here.

***

All in all, this set of books is a strong start for V&Q Books (I like their series cover design as well). I look forward to seeing what else they have in store for us.

Recent Comments