By accident rather than design, I read less in 2018 than I had in quite some time. However, unlike last year, it feels right to do my usual list of twelve favourites. One thing that really stands out to me is what a good year it’s been for short story collections – I have four on my list, more than ever before. 2018 was also the year when I started reviewing for Splice, and you’ll see that reflected in my list, too.

As always, the ranking is not meant to be taken too seriously – I like to have a countdown, but really I’d recommend them all. I haven’t differentiated between old and new books, though as it turns out, most are from this year. The links will take you to my original review of each book.

You can also read my previous favourites posts from 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, and 2009. Thank you for reading, and I’ll see you next year. It’ll be the tenth anniversary of this blog, so I have some plans for looking back as well as forward.

12. And the Wind Sees All (2011) by Guðmundur Andri Thorsson

Translated from the Icelandic by Andrew Cauthery and Björg Árnadóttir (2018)

I read this book only a few days ago and it made such an impression that it went straight on to my end-of-year list. Part of Peirene’s ‘Home in Exile’ series, And the Wind Sees All is set in an Icelandic fishing village, during a couple of minutes during which Kata, the village choir’s conductor, cycles down the main street. Like the wind, the novel flows in and out of the lives of the villagers Kata cycles past, revealing secrets, losses, fears and joys. The writing is gorgeous.

11. Fish Soup (2012-6) by Margarita García Robayo

Translated from the Spanish by Charlotte Coombe (2018)

The English-language debut of Colombian writer García Robayo, Fish Soup collects together two novellas and seven short stories. Among others, we meet a young woman so desperate to escape her current life that she can’t see what it’s doing to herself and others; a businessman forced to confront the emptiness in his life; and a student being taught one thing at school while experiencing something quite different in her life outside the classroom. All is told in a wonderfully sardonic voice.

10. Three Dreams in the Key of G (2018) by Marc Nash

This is a novel of language, motherhood, and biology, told in the voices of a mother in peace-agreement Ulster; the elderly founder of a women’s refuge in Florida; and the human genome itself. Perhaps more than any other book I read this year, the shape of Three Dreams is a key part of what it means: it’s structured in a way that reflects DNA, and the full picture of the novel emerges from the interaction of its different strands.

9. Frankenstein in Baghdad (2013) by Ahmed Saadawi

Translated from the Arabic by Jonathan Wright (2018)

This was a book that had me from the title. A composite of corpses comes to life in US-occupied Baghdad. It starts to avenge the victims who make up its component parts, then finds those disintegrating, so it has to keep on killing to survive… and becomes a walking metaphor for self-perpetuating violence. Saadawi’s novel is powerful, horrific, and drily amusing where it needs to be.

8. The Last Day (2004) by Jaroslavas Melnikas

Translated from the Lithuanian by Marija Marcinkute (2018)

A collection of stories where the extraordinary intrudes on the everyday – such as a cinema showing the never-ending film of someone’s life, or a mysterious treasure trail leading the narrator to an unknown end point. Melnikas’ stories become richer by reflecting on what this strangeness means for the characters, an approach that was right up my street.

7. The White Book (2016) by Han Kang

Translated from the Korean by Deborah Smith (2017)

Another deeply felt book from a favourite contemporary writer. The White Book is structured as a series of vignettes on white things, from snow to swaddling bands, all haunted by the spectre of a sister who died before the narrator was born. Reading Han always feels more intimate than with most other writers; her prose cuts like glass, bypassing conscious thought and going straight to the place where reading blurs into living.

6. T Singer (1999) by Dag Solstad

Translated from the Norwegian by Tiina Nunnally (2018)

My first experience of Solstad’s work, and it’s like reading on a tightrope. A synopsis would make it seem that nothing much is going on, as Solstad’s protagonist seeks anonymity by becoming a librarian in a small town. But the busyness of Singer’s inner life creates a contrast with his essential loneliness, an abyss for the reader to stare into.

5. The Girls of Slender Means (1963) by Muriel Spark

Every time I read Muriel Spark, I’m reminded of why I want to read more. Set in a post-war London boarding house for young women, this is a tale of lost (and sometimes found) opportunity and missed communication. I love the way that Spark twists her characters’ (and reader’s) sense of time and space, the undercurrent of dark wit… No doubt there’s even more to see on a re-read.

4. The Sing of the Shore (2018) by Lucy Wood

Everything that Lucy Wood writes ends up in my list of favourites. I love the way that she evokes a sense of mystery lying beneath the interaction of life and place. The stories in The Sing of the Shore are set in off-season Cornwall, a place where children take over other people’s unoccupied second homes, the sand advances and recedes, and both people and things are transient.

3. The Ice Palace (1963) by Tarjei Vesaas

Translated from the Norwegian by Elizabeth Rokkan (1993)

I loved this Norwegian classic about a girl trying to come to terms with her friend’s disappearance. Vesaas’ novel is full of the raw sense of selves and friendships being formed, and examines what it takes to find one’s place in a community or landscape. The prose is beautiful, crystalline and jagged, like the frozen waterfall that gives The Ice Palace its title.

2. Mothers (2018) by Chris Power

Stories of family and relationships, travel and searching – each illuminating and resonating with the others. Three stories following the same character’s journey through life form the backbone of Power’s collection. In between, there’s a frustrated stand-up comedian, a couple walking in Exmoor who find their relationship tougher terrain, a chess-like game of flirtation in Paris, and more. I can’t wait to see what Power writes next.

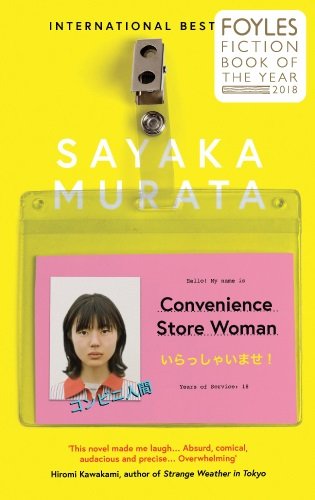

1. Convenience Store Woman (2016) by Sayaka Murata

Translated from the Japanese by Ginny Tapley Takemori (2018)

A novel about a woman who has worked in a convenience store for 18 years, trying to find her own sort of normality. The protagonist’s sense of self is challenged, and the reader is also challenged to empathise with her. Convenience Store Woman is a vivid character study that builds to the most powerful ending I’ve read all year. I won’t forget this book for a long, long time.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Recent Comments