It’s time for another selection of short reviews that first appeared on my Instagram.

Brian Dillon, Suppose a Sentence (2020)

It always fascinates me that I can read something and it will move me so much. How does that work? How does writing do what it does? Brian Dillon’s new essay collection from Fitzcarraldo Editions approaches these sorts of questions by looking at individual sentences.

Dillon says in his introduction that he’s been collecting striking sentences in notebooks for 25 years. He examines some of these, and others, in this book – sentences by writers from William Shakespeare to Virginia Woolf, James Baldwin to Hilary Mantel.

Dillon’s responses to the sentences are deeply personal and often wide-ranging. He might go into the author’s biography, or look at the wider context of their work. There’s a certain amount of discussing the grammatical nuts and bolts, but it’s always at the service of working out what makes each sentence distinctive.

I’m struck in particular that Dillon doesn’t always explain the context of the sentences straight away – he waits until the time is right. That means the reader often has to come to each sentence on its own terms, which is especially interesting where a sentence is not taken from its author’s best-known work.

Above all, Suppose a Sentence inspires me to think about sentences that I find striking, what they do and why. It’s a book to stir one’s enthusiasm for reading.

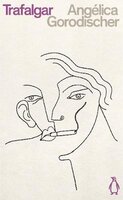

Angélica Gorodischer, Trafalgar (1979)

Translated from the Spanish by Amalia Gladhart (2013)

Penguin Classics have launched a new science fiction series which I’m excited about, particularly as half of the launch list is in translation. I also love the series design, all stark line drawings and purple accents (a nod to the purple logo used by Penguin for science fiction back in the ’70s).

The first book I’ve read from the series is this Argentinian novel-in-stories. Trafalgar Medrano (born in the city of Rosario in 1936) is a merchant with a taste for strong coffee, unfiltered cigarettes, and women. He also travels and trades among the stars, returning to his home city to tell the tall tales in this book.

On the downside, I have to say that Trafalgar’s constant womanising gets tedious. But the sheer imagination of these stories is quite something. Trafalgar travels to all manner of worlds: on one, he seems to jump through time each day. On a different world, everything is rigidly ordered, with just one person willing to break away by speaking nonsense.

What makes Gorodischer’s book for me is the casual way it narrates such extraordinary events. There’s no need for explanation, you just go with the flow and whole worlds open up.

Kei Miller, The Cartographer Tries to Map a Way to Zion (2014)

This poetry collection won the Forward Prize in 2014. Broadly speaking, it’s about two ways of knowing the world: the scientific precision of those who set out to find “the measure that / exists in everything”, and the instinct of someone like Quashie, who “knew his poems by how they fit in earthenware”, because each word is just as long as it needs to be.

Much of the book is taken up by the long title poem, which concerns the different views of a cartographer and a rastaman. The mapmaker sees it as his job “to untangle the tangled / to unworry the concerned”. But the rastaman knows that the “tangle” is itself part of his island, and thinks that the cartographer’s work “is to make thin and crushable / all that is big and as real as ourselves”.

Interspersed among the volume is a series of prose poems which reveal the stories behind different place names, such as Bloody Bay, “after the cetacean slaughter” These pieces highlight the history that lies behind a bare list of names, history unknown to the cartographer.

“If not where / then what is Zion?” asks the cartographer. It’s “a reckoning day”, replies the rastaman, “a turble day.” Reaching Zion, the rastaman says, is not a matter of travel, but a “chanting up of goodness and rightness and, of course, upfullness…to face the road which is forever inclining hardward.” Not every place that matters can be located on a map.

Published by Carcanet Press.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Recent Comments