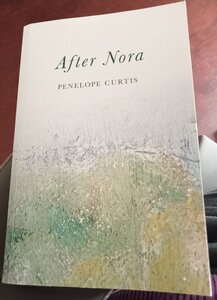

In her first novel, art historian Penelope Curtis imagines two episodes from her family’s history. The first part concerns Nora (Penelope’s grandmother, whom she never knew), a painter who tries to articulate what her art is ‘about’. Nora comes to feel that landscape is key:

Landscape had, without her quite realizing, become something essential…This had nothing to do with topography, but everything to do with understanding how we manage and what helps. And then she saw that landscape did a good job of disguising itself, wrapping something essential in so many trees. It re-attached litself to us when it was well painted. Then we remembered the painting, more than nature, but we found the painting again once we were back in nature.

In the 1920s, Nora divorces her first husband and marries Lewis, an architect. She is clearly attracted to him, but the exact source of that attraction is mysterious – there’s a certain feeling of distance to Curtis’s writing in this part. It’s not until Nora reads through a packet of Lewis’s letters from the Great War that she has a revelation: the letters’ repetitive nature evokes a way of seeing and feeling landscape that mirrors what Nora saw and felt in her own paintings.

The novel’s second part revolves around the relationship between Nora’s son (Penelope’s father) Adam and Maria de Sousa, both scientists in Glasgow in the 1960s. Scenes alternate between then and the present, after Adam has died, when the author-narrator is in Portugal and tracks down Maria, hoping to gain more understanding of her father’s life at that time.

Both parts then involve a character seeking understanding through art: Nora looking for a deeper understanding of herself through her painting, and the narrator seeking to understand her father better through imaginative writing. But Nora’s story here is itself an act of imagination, which perhaps underlines that there’s a limit to understanding, after all.

Published by Les Fugitives.

Recent Comments