I first came across Gabriel Josipovici’s name from blogs such as This Space. I read some of his critical work, and was particularly taken with his idea of art as a toy. Broadly speaking, I understand this to mean art that keeps its component parts in view, in the same way that a hobby horse can still obviously be a stick. Then we can take those component parts and make our own experience with them.

This idea struck a chord with me because it seemed to me that many of my favourite books worked that way. Well, now I’ve read a couple of Josipovici’s novels, and discovered that they work that way as well…

***

Infinity: the Story of a Moment (2012) is the account of an Italian composer, one Tancredo Pavone (inspired by the real-life figure Giacinto Scelsi), whose words are related by his manservant Massimo in interview. Pavone comes across as an absurd, pompous figure in many ways, with his vast collection of clothes that may be worn only minimally, and his strident opinions (“German composers have been so busy airing their souls, he said, that they forgot to air their clothes”).

But there’s something else in there: Pavone argues for a more primal sort of art than what he sees (or hears) around him. He sees music as “a vehicle for the body to express itself.” Pavone goes on: “The language of music is not the sonata and it is not the tone row…it is the same kind of language as weeping, sobbing, shrieking and laughing.” I can understand this by instinct: why I think about the art that I’ve responded to most strongly (books especially, but not only), it was a response that went through my whole body – a sense of being more intensely alive.

The most powerful aspect of Infinity for me is that it’s structured in a way that brings out the same feeling. Pavone’s personality fills the book, larger than life, but his vulnerability starts to show as time goes on. By the end, Massimo is telling of the period after Pavone had a stroke, shoring the composer up, giving him a voice in a way that Pavone himself couldn’t by then. The composer’s intense engagement with existence is what most stands out , and the circuitous way that Massimo tells Pavone’s tale creates a space which allows us to experience that intensity. To bring in a toy metaphor, Infinity is something of a kaleidoscope, turning to reveal different aspects of its subject’s world.

***

If Infinity is a kaleidoscope, The Cemetery in Barnes (2018) is a set of building blocks. It begins with the unnamed protagonist, a translator, describing his daily routine as a single man in Paris. After three pages, another voice interjects, that of his second wife – and suddenly we’re in Wales, where the couple are entertaining friends in their converted farmhouse.

There’s something quite startling about the way this is done: sketching his Parisian life vividly, then pulling us out of it into a vivid new life. The novel continues, sliding between Wales, Paris, and an earlier stage of the translator’s life, with his first wife in London. The rhythm of these switches is always uneven – it’s not something we’re allowed to take for granted.

Something that I found intriguing early on was the way Josipovici makes the very idea of there being different stages in one life seem strange – it just feels so improbable that the single man in Paris might become the married man bickering with his wife in Wales, for example. But then the novel goes further: “One sprouts so many selves,” comments the protagonist. There are glimpses of contradictory pasts and futures, some much darker than others.

The Cemetery in Barnes put me in mind of a rather different novel, Christopher Priest’s The Affirmation (1981). Priest’s novel has two versions of the same character, one living in what looks like the real world, and one in what looks like a fantasy world – but neither life has more reality than the other, so both have equal weight. Similarly, the question arises in Cemetery: are we reading about one imaginary life or many? The reader can choose which blocks to use to build meaning, but ultimately any meaning only lasts until the book is closed.

***

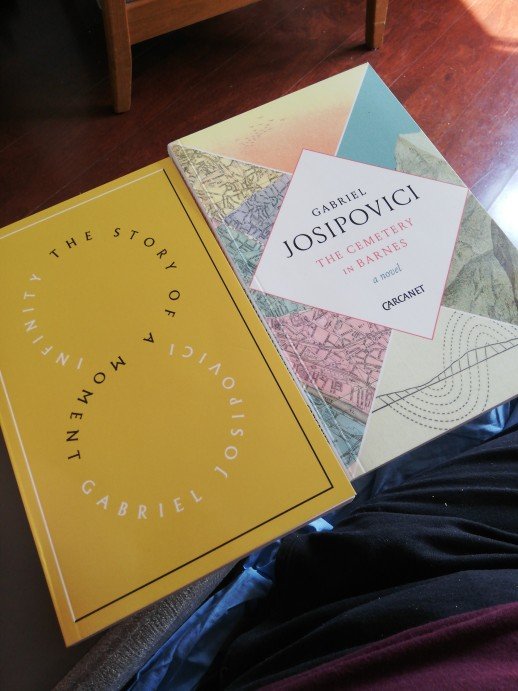

Infinity and The Cemetery in Barnes are both published by Carcanet.

Recent Comments