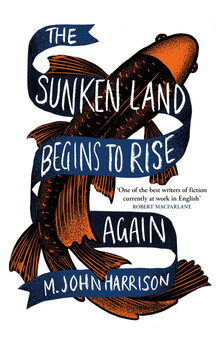

The winner of this year’s Goldsmiths Prize was announced last Wednesday, and it was the one I hadn’t finished reading at the time. So first of all, congratulations to Mike Harrison on his win — I’m pleased he’s had this recognition. Now on to the book itself.

On the face of it, The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again would seem the most conventionally written novel on the Goldsmiths shortlist — there are no contrasting voices or unusual layouts here. But what Harrison does, gradually and comprehensively, is to undermine the basic qualities that we might expect a conventional novel to have. Coherence, progression, resolution… all dissipate as you look at them more closely.

Harrison’s two protagonists are caught in the midst of something strange, not that they seem to notice. Shaw is getting back on his feet following a breakdown. He moves into a small room in a damp London house. He meets one Tim Swann combing through the soil in a cemetery, and later discovers he lives next door. Tim offers Shaw a job in an office on his barge, obscure administrative tasks and trips to niche shops that are barely hanging on:

The internet was killing them. The speed of things was killing them. They were like old-fashioned commercial travellers, fading away in bars and single rooms, exchanging order books on windy corners as if it was still 1981 — denizens of futures that failed to take, whole worlds that never got past the economic turbulence and out into clear air…

In one sense, then, the ‘sunken land’ of the title refers to people and places worn down by austerity.

The novel’s second protagonist is Victoria, with whom Shaw is having an intermittent affair. Victoria has moved from London to the Midlands, to work on renovating her late mother’s home. She finds the people quite distant, and seemingly more knowledgeable about her mother than she is. She becomes sort-of friends with Pearl, a waitress, who lives in a house whose rooms seem to shift and where people come and go without warning.

You would never know there was anything unusual about Victoria’s life, though, if you judged by the banal emails she sends to Shaw (not that he usually reads them). Failures in communication are a recurring feature of this novel, whether it’s Victoria and Shaw not telling each other what’s really going on in their lives, or Shaw’s struggle to connect with his mother, who has dementia and can never get his first name right.

A breakdown of communication is one thing, but this is also a novel where the world itself fails to come together. Images of water abound, and there are rumours of humans being born with the appearance of fish. Tim Swann researches such fringe phenomena, and there are hints at a unifying explanation of all the book’s strange happenings. But when one’s actually reads Tim’s writings, the semblance of coherence disappears:

Stories reproduced from every type of science periodical appeared cheek-by-jowl with listicle and urban myth. These essentially unrelated objects were connected by grammatically correct means to produce apparently causal relationships. Perfectly sound pivots, such as ‘however’ and ‘while it remains true that’, connected propositions empty of any actual meaning…

The same goes for Sunken Land more broadly. Whatever’s really going on here, it’s not within the sight or comprehension of our protagonists — and therefore of us. If there’s a promise of escape from (or for) this sunken land, it will be fulfilled somewhere else. Harrison’s novel is unnerving because there are echoes of motion throughout, but ultimately what we experience through its characters is stasis.

Published by Gollancz.

Click here to read my other reviews of the 2020 Goldsmiths Prize shortlist.

This is Viriconium: the city to end all cities; namesake of the dominant empire in Earth’s twilight. This is Viriconium: an omnibus of novels and stories by

This is Viriconium: the city to end all cities; namesake of the dominant empire in Earth’s twilight. This is Viriconium: an omnibus of novels and stories by  Euan Armstrong takes his young family to Bahrain, ostensibly to undertake missionary work; but Euan’s wife Ruth begins to question all that she holds dear when she discovers the true nature of that work. Meanwhile, teenage Noor Hussain has returned to Bahrain from England to live with her father; she has struggled to fit in and is contemplating suicide. But then Noor finds new hope in the person of Ruth, just as Ruth is falling for Noor’s brother Farid.

Euan Armstrong takes his young family to Bahrain, ostensibly to undertake missionary work; but Euan’s wife Ruth begins to question all that she holds dear when she discovers the true nature of that work. Meanwhile, teenage Noor Hussain has returned to Bahrain from England to live with her father; she has struggled to fit in and is contemplating suicide. But then Noor finds new hope in the person of Ruth, just as Ruth is falling for Noor’s brother Farid. Another fine novella from

Another fine novella from

Recent Comments