Ray Robinson, Jawbone Lake (2014)

Ray Robinson was last seen on this blog in 2010 when I read Forgetting Zoë, his excellent novel about a young girl held captive in Arizona, in danger of losing her very self. For his new book, Robinson travels closer to home, with a tale which is more concerned with remembering, as its characters face life without loved ones whom they remember painfully well – although, in one case, they didn’t know him quite well enough.

Ray Robinson was last seen on this blog in 2010 when I read Forgetting Zoë, his excellent novel about a young girl held captive in Arizona, in danger of losing her very self. For his new book, Robinson travels closer to home, with a tale which is more concerned with remembering, as its characters face life without loved ones whom they remember painfully well – although, in one case, they didn’t know him quite well enough.

We begin on New Year’s Eve, with a Land Rover driving straight into Jawbone Lake, near the Peak District town of Ravenstor. The driver of the vehicle was CJ Arms, a local businessman who’d built up a successful company in Spain. CJ’s son Joe returns home from London to a family who cannot explain the crash, clinging to the hope that, as long as CJ’s body is not found, he may still be alive. Joe’s grandfather Bill asks him to travel to Spain and find out the truth of CJ’s life there; what Joe discovers will challenge everything he thought he knew about his father.

The events of New Year’s Eve were witnessed by Rebecca Miller, otherwise known as Rabbit, a woman haunted by the sudden death of her baby son a year previously. She is developing an uncertain attraction for a colleague at work, but perhaps her main hope is for somewhere to hide from the world. And a third figure, Grogan – who pursued CJ down to the lake – is watching both Joe and Rabbit, waiting for the right moment to tidy things up.

For quite a way into Jawbone Lake, I was thinking that the character of Grogan didn’t seem to fit: he’s the type of sinister hard man who is a mainstay of Brit gangster thrillers, but seems out of place in what is generally quite a reflective portrait of families dealing with grief and loss. Then it struck me that this may be the point: the thriller elements of the novel are an intrusion on what appeared to be the reality of life. Perhaps this is most clear when Joe visits Spain, and learns about his father’s other life; it doesn’t square with the CJ he knew, but is nonetheless real, and Joe has to face up to that.

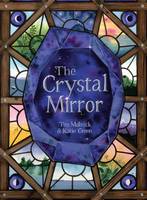

So, the loss of CJ leaves a hole in the Arms family’s life that gets harder to fill the more they learn about him. The situation is subtly different in Rabbit’s case: there’s a hole in her life caused by the death of her son (and that of her mother, who passed away some years before); but it’s only by reaching into and learning more about herself that Rabbit is able to find a way forward. The general theme of hidden truth is mirrored elegantly in Robinson’s use of landscape: Jawbone Lake is not a natural feature, but a reservoir with an old village at the bottom (I must tip my hat here to the superb cover design, which heightens the artificiality of a supposedly ‘natural’ scene, and is really quite eerie); every new environment in which CJ lived seems to have brought out a different side to him.

In Jawbone Lake, you have a novel that starts off as the mystery of why this man would drive into a lake; grows into an examination of how people may try to handle grief and uncovering secrets; and that knows how to thrill, even as it treats its thriller aspect as something strange and inscrutable. So that’s another intriguing book from an author whose work should not remain a secret.

Elsewhere

Ray Robinson’s website

Interview and review at Raven Crime Reads

Robinson writes about the places that inspired Jawbone Lake

Recent Comments