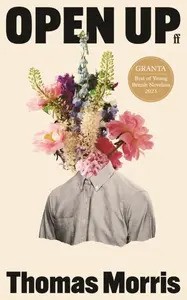

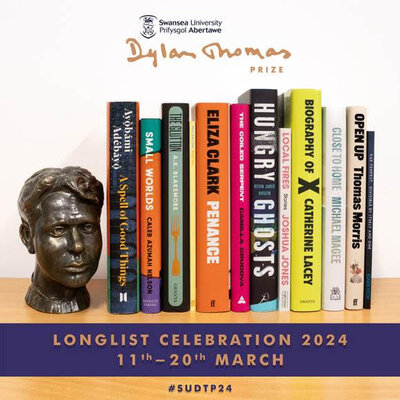

For the last few years, I’ve taken part in a blog tour for the Swansea University Dylan Thomas Prize (awarded to works in English by writers aged under 40), looking at one of the longlisted titles. This year, my book of choice is the second story collection by Welsh writer Thomas Morris (following on from 2015’s We Don’t Know What We’re Doing).

The five stories in Open Up each revolve around male protagonists seeking a connection of some sort (seeking for the world to open up, if you will) – but there’s always a twist to how Morris approaches his material. The first story, ‘Wales’, sees a young boy going to a football match with his father (whom he hasn’t seen for three months) and feeling that everything will be fine if only Wales win. A glimpse into the future at story’s end stretches time to show that there can be unexpected turns of fortune (though maybe not perfection) after all.

Sometimes Morris’s tales shift towards fantasy. For example, ‘Aberkariad’ is a story about seahorses. It lays human emotions on top of the particular biology of seahorses, bringing an unusual angle to the tale of a boy searching for his absent mother. In ‘Birthday Teeth’, Glyn describes himself as a vampire. Maybe he is, maybe it’s part of the disconnection he feels from his past and the world around him. Either way, he’s going to get himself some fangs on his 21st birthday. The process changes Glyn’s outlook, with the sense that he is able to become more fully himself.

Even in the stories that seem more ordinary, there are intriguing undercurrents. ‘Little Wizard’ sees Big Mike (all five-foot-three of him) struggling with work and dating. So much of his life seems to be mediated through screens, whether that’s taking to friends on apps or watching football on TV. These represent Mike’s distance from the world but, in a nice touch, that very distance is also what helps him find a way forward. In ‘Passenger’, Geraint is on holiday in Croatia with his partner Niamh. But he’s not really present, as he’s dwelling more on the past. So there are two journeys going on in this story at the same time, and each helps resolve the other. The seems to me typical of the striking patters Morris paints in the stories of Open Up.

Open Up is published by Faber & Faber. The Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist will be revealed on 21 March, with the winner to be announced on 16 May.

Recent Comments