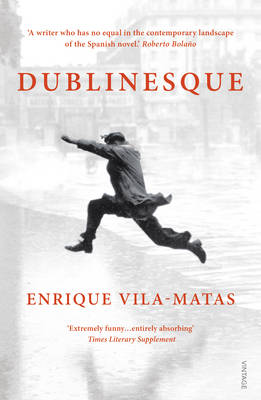

I’ve been asking myself: what is it about Dublinesque? In a previous post, I quoted a passage from Enrique Vila-Matas’ 2010 novel which says that reading can often demand that we “approach a language distinct from the one of our daily tyrannies.” When I’m thinking about how I respond to a piece of fiction, I often start with the language, because that’s what fiction is made from. In Rosalind Harvey’s and Anne McLean’s translation from the Spanish, Vila-Matas’ language seems fairly straightforward; but there’s something about it that I can’t quite put my finger on. Perhaps I’ll have managed it by the time I finish this blog post.

I’ve been asking myself: what is it about Dublinesque? In a previous post, I quoted a passage from Enrique Vila-Matas’ 2010 novel which says that reading can often demand that we “approach a language distinct from the one of our daily tyrannies.” When I’m thinking about how I respond to a piece of fiction, I often start with the language, because that’s what fiction is made from. In Rosalind Harvey’s and Anne McLean’s translation from the Spanish, Vila-Matas’ language seems fairly straightforward; but there’s something about it that I can’t quite put my finger on. Perhaps I’ll have managed it by the time I finish this blog post.

Samuel Riba is one of “an increasingly rare breed of sophisticated, literary publishers” who despairs at “the gothic vampire tales and other nonsense now in fashion.” He closed his publishing house after thirty years, having published numerous great writers, but without having achieved his ambition of discovering a new genius. Now Riba is a recovering alcoholic in search of a direction. There is a temptation here – especially when Riba reflects bitterly on “the falsely discreet young lions of publishing” – to generalise, and view ‘publishing’ as a metaphor, with Riba the ageing man who feels overtaken by the world at large. But I don’t think Dublinesque is quite reducible to such generalities, because literature is too bound up in Riba’s worldview: “he has a remarkable tendency to read his life as a literary text, interpreting it with the distortions befitting the compulsive reader he’s been for so many years.”

A couple of years earlier, Riba dreamed of Dublin, and now takes it upon himself to go there – or, more precisely, the Dublin of James Joyce – and hold a funeral for “the Gutenberg galaxy”. His model is the funeral in chapter six of Ulysses, he visits the city on Bloomsday… the sense of a journey shaped by the forces of literature only grows with the ‘stage directions’ that frame the Dublin-set sections, and the mysterious figures, like the man in the mackintosh from Ulysses, that Ribs keeps glimpsing.

As well as these figures, Riba is haunted by the notion that his life may be the subject of a novel. He’s right about that, of course, though the novelist is not the “young novice” whom he imagines. This means, then, that Riba is haunted by figures of whom he has no idea. Just occasionally, the third-person narration breaks into an ‘I’, a brief reminder of the writer who lies behind Riba. And behind the writer lies the reader; so perhaps this is the sense that’s been eluding me: to read Dublinesque is to be a ghost haunting the novel, with Vila-Matas’ prose providing a subtle balance of distance and closeness that lets us in just far enough. But that only really becomes apparent at the end, when the dream has faded and the book can haunt us.

12th July 2015 at 2:14 pm

This really sounds rather intriguing – and I’m glad it’s not just me that sometimes struggles to pin down what it is about a writer’s language that’s so special. I shall look out for this one.

18th July 2015 at 10:32 pm

Kaggsy, it is very good – definitely recommended. It fascinates me that certain arrangements of words can have such a deep effect; trying to pin down what’s happening and why is often difficult, but it’s something I really want to try to do.

12th July 2015 at 8:56 pm

I love Ribs as a character he is of that dying breed of lit folk before it all became about money like it is now

18th July 2015 at 10:32 pm

Stu, I agree, he’s a great character – publishing could do with more like him.

13th July 2015 at 7:54 pm

I’ve just experienced a very similar not-quite-able-to-put-my-finger-on-it feeling reading Vila-Matas’ A Brief History of Portable Literature!

I think the balance of distance and closeness is spot on.

18th July 2015 at 10:40 pm

Grant, that’s interesting. You know Vila-Matas’ work better than I do – is it a common experience?

14th July 2015 at 7:51 pm

With one notable exception, the Vila-Matas novels I’ve read up to now have been of an ironical or satirical bent. Is this the case with Dublinesque at all or is the novel more a case of being “haunted” by literature in a more serious vein? Thanks for reading along with us Spanish Lit Month folks, David, and I hope you get a chance to read V-M’s Bartleby & Co. before long. Cheers!

18th July 2015 at 10:50 pm

Richard, you’re quite right: there is a humorous streak running through Dublinesque, and with hindsight I can see that I didn’t quite bring that out in the post. Perhaps that’s because the humour feels so bound together with everything else, if that makes sense.

Incidentally, which novel was the exception?

26th July 2015 at 1:40 am

One of my favourite books about writing. Here’s another nice quote from it:

“What logic is there in things? None really. We’re the ones who look for links between one segment of our lives and another. But this attempt to give form to that which has none, to give form to chaos, is something only good writers know how to do successfully.”